Charles Hasker's footprints in Church Hill

Walk left from my house and I pass one of his buildings. Walk right and I pass another. If I walk toward the taco place, yet another. Here is an account of Charles Hasker's presence in Church Hill.

Note: Again, I’m recycling old posts from elsewhere before I start doing new stuff here. Did this one a couple of years ago.

Charles H. Hasker is an interesting dude who shaped the physical landscape of where I live. Born in London in 1831, he reportedly joined the Royal Navy. He couldn’t have been in it long because he’s in the US in the early 1850s, serving as a Boatswain on several US Navy ships. On one cruise, aboard the USS Dale, he participated in the suppression of the international slave trade off the west coast of Africa

Hasker settled in Portsmouth, Virginia, a Navy town, and married a local girl. The couple had two surviving children by 1860.

While aboard the USS Susquehanna in Boston in the summer of 1861, Hasker and a bunch of southern-born officers submitted their resignations and headed to the Confederate States.

In November of that year Hasker enlisted in the CS Navy, becoming the Boatswain aboard the CSS Virginia (aka, the Merrimac) and participated in the famous Battle of Hampton Roads. Then, the service transferred him to Drury’s Bluff where he commanded a gun in the repulse of a US Navy assault in 1862.

He was captured by US forces near Charleston, S.C. when Confederates evacuated Battery Wagner, and spent a year imprisoned in Boston. He was exchanged in late 1864 and assigned to a naval battalion in Richmond.

Hasker’s next moves are a bit of a mystery. In the late 1860s he opened a paper box manufactory on Main Street near the state capitol. At the same time, he lived in Norfolk. He didn’t last long as a commuter, though. Mrs. Hasker died in 1872 and he very quickly married a widow, Sarah Virginia Christian Creekmore, who lived on N Street in Church Hill.

Hasker had sailed the wide blue sea, but once with Sarah, he settled in to the 25th Street corridor and traveled no further.

(Except for that one time that he pranked Congress during Reconstruction. It reportedly offered a reward for the man who had sunk the CSS Virginia—thinking a sailor aboard the Monitor. But Hasker claimed that as the ship’s boatwain, he had been the one to set the fatal fire when it was abandoned, and so cheekily traveled to DC to collect. Don’t know if this is true or not, but Hasker told that story.)

He joined all the fraternal organizations: Order of the Iron Hall, the Masons, the Good Templars; he attended Confederate veteran activities and joined the Pickett Camp of the UCV in 1894; and in the 1890s, he toured a popular “illustrated lecture” (using pictures and electro-chemical lights) about historical naval ships and battles, featuring his own memories from Hampton Roads. One reviewer called it a “highly chaste, historical, and instructive entertainment.”

He lived at various places adjacent to 25th Street above M Street, but eventually settled on the corner of 24th and (now) Cedar Street, where the “Richmond Virginia Seminary” now stands unused. Many of his organizations met at the house that they called “Hasker Hall.” (A different building on that corner now seems to have replaced it… but it might be the same. I don’t know.)

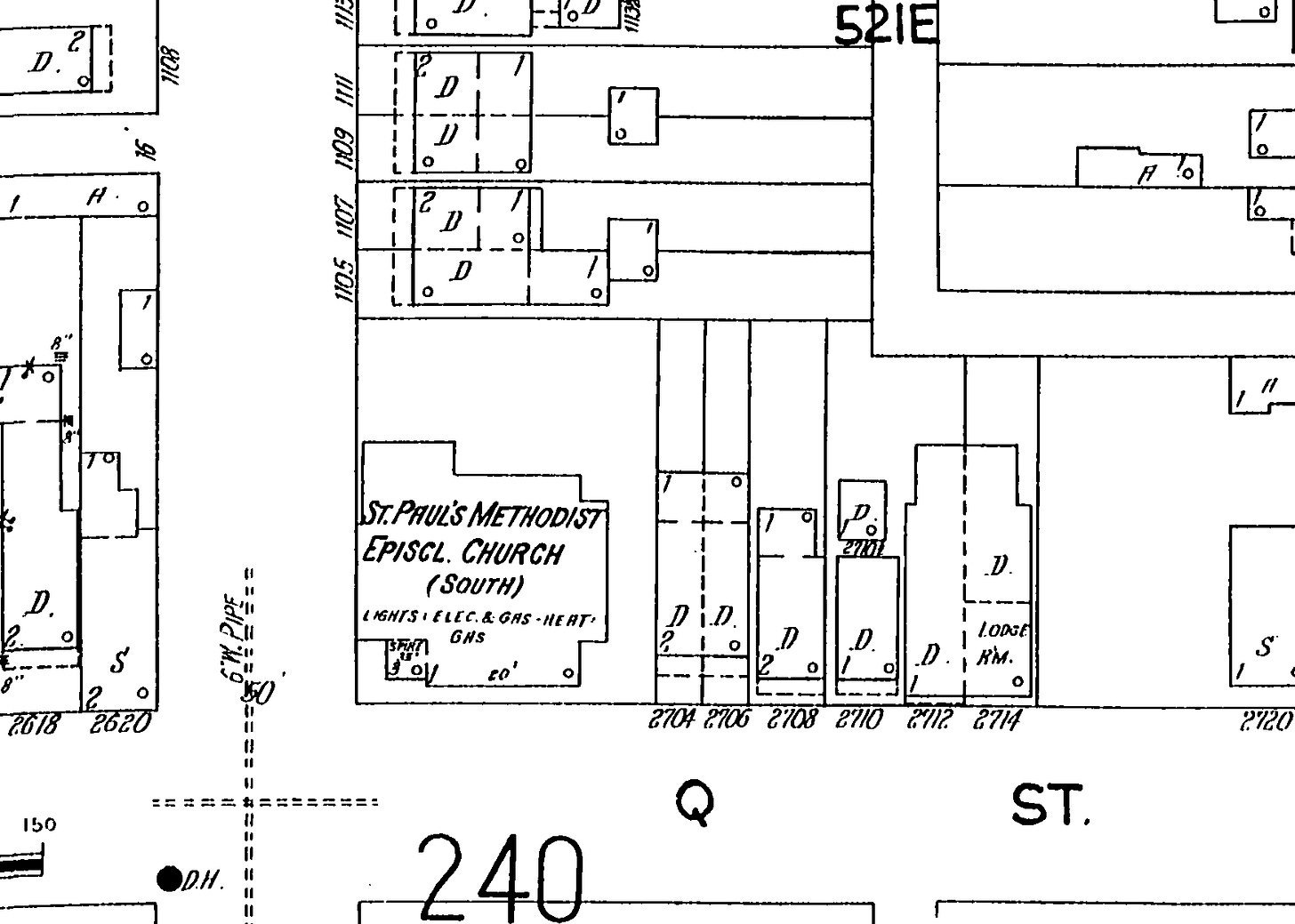

Hasker’s primary passion, however, was the Methodist Church. He joined what became Union Station Methodist Church. I’m having trouble pinning the original location down. One source has it in the present-day Mt. Sinai church on 25th Street. Another has it at the corner of 24th and Venable. I don’t know.

But I do know that Hasker took an interest in the Sunday School movement and became the superintendent of the Sunday School at Union Station and served on several Virginia Conference Sunday School committees.

In 1894, Union Station built a grand new building on 24th Street across the street from Hasker Hall. He donated $1,000 to the building fund. You know it today as Cedar Street Baptist and it’s the best landmark in the East End imo.

Hasker’s lifelong interest in naval history became relevant (at least he thought) when the USS Maine exploded in Cuba in 1898. Hasker had OPINIONS, and rushed to Washington, D.C., to share them with whoever would listen.

He did not, however, live long enough to appreciate the US Navy’s remarkably effective performance in the Spanish-American War. Hasker died in June, 1898. He is buried in Oakwood, but I haven’t been able to find him.

One reporter who visited in 1893 noted that “There is tin everywhere about the place in every conceivable shape and condition. Tin boxes, tin buckets, tin tags, tin signs, tin throw cards, and in fact everything that can be well made from tin.”

Shortly after Charles Hasker died, his partner sold the factory to the American Can Company, the nationwide trust then monopolizing the tin can manufacturing business.

Charles Hasker loved the Methodist Sunday School. He served as Superintendent at Union Station and on various Conference boards and committees.

The new building, being wood framed, was modest compared to Union Station’s soaring brick towers, perhaps reflecting the more working class sensibilities (and financial abilities) of Hasker’s members. It opened in 1906, with a cornerstone marking the date.

Like most white and Black churches at that time (and if it’s not clear, Hasker Memorial was a white church), it became a center of Progressive civic life. Its preacher gave a pro-Union (organized labor, not Civil War) sermon in 1903. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union met there as well. It hosted a baseball team that competed in a Church Hill Sunday School league. It’s choirmaster (Elmore P. Gary) stood on the dais and demanded better jobless relief payments at the depths of the Great Depression.

In 1910, the church changed its name to “St. Paul’s Methodist” in accordance with Conference directives on church names not honoring laypeople.