Robert Damell's family

Robert Damell played a crucial role in my book. At the time we couldn't figure out much about his family, but a simple spelling change on a search term opened things up things. Here's what I found.

Note: I’m recycling some things I’ve posted elsewhere while I play with this platform and work on some new material.

Robert Dammell

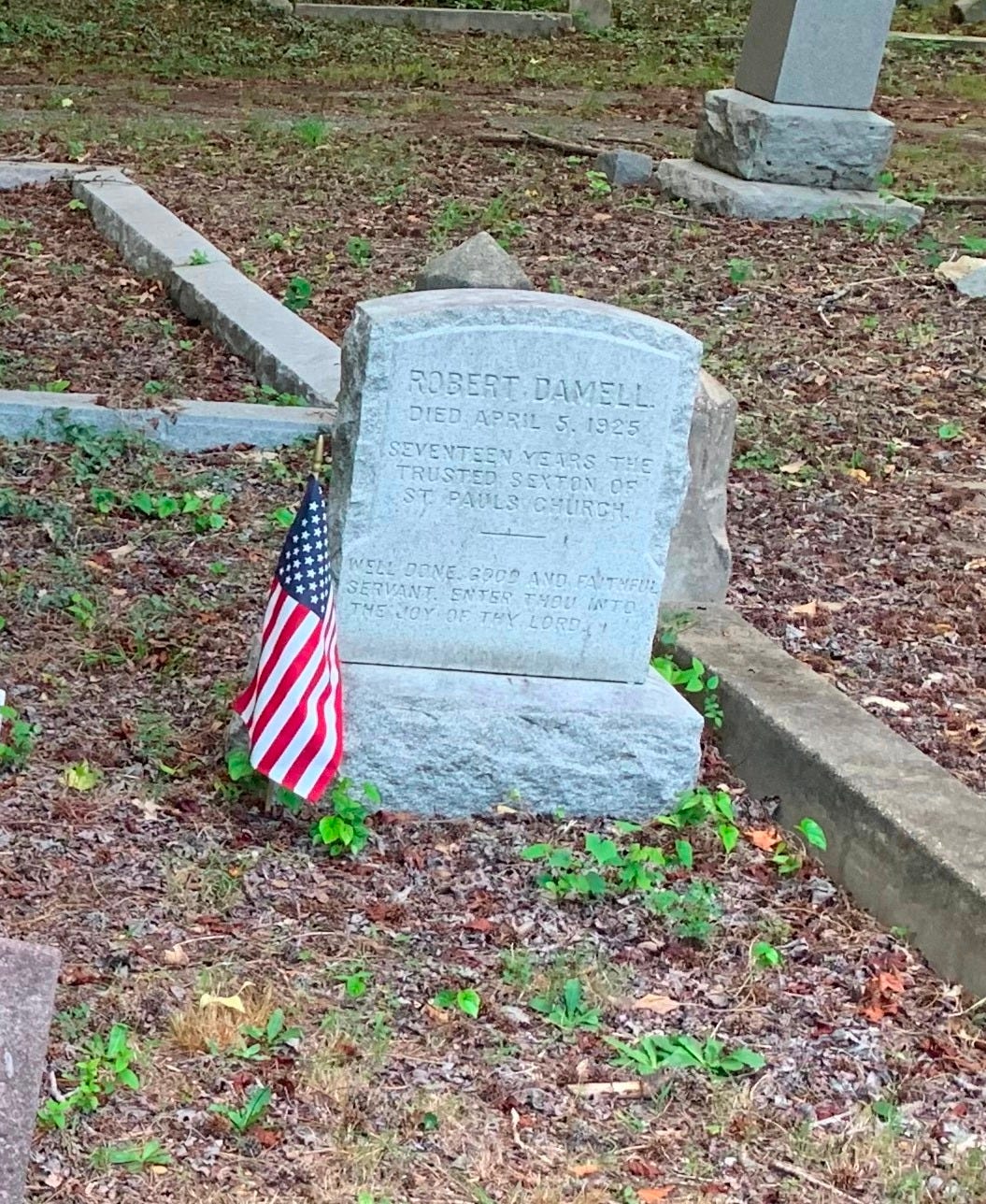

You hang around me and you’ll hear about Robert Damell. He was the Black man who served as the long-time sexton at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond. When Damell died in 1925, St. Pauls made a big show of how much they loved him by hosting his funeral in the sanctuary. His family and friends occupied the lower seats and the white folks sat in the galleries. Virginia’s white leadership, smug that they had proven something about good race relations, used his funeral as a justification for the 1926 Public Assemblages Act, one of the dumbest and most extreme of Virginia’s notoriously extreme segregation laws.

We never really found much more on Robert Damell other than the fact that he was from Northumberland County, he had served in the U.S. Army during the Indian Wars and left behind a wife (Fannie) and daughter (Charlotte). (We do know quite a lot about Charlotte’s descendants, but that’s a different story). Robert didn’t leave as large a footprint in the historical record as we’d like… besides all the white folks who loudly regarded him as a “faithful servant” and nothing more.

He’s buried at Evergreen Cemetery, not far from Maggie Walker and John Mitchell, Jr., beneath a headstone supplied by St. Pauls and inscribed with a paternalistic epitaph.

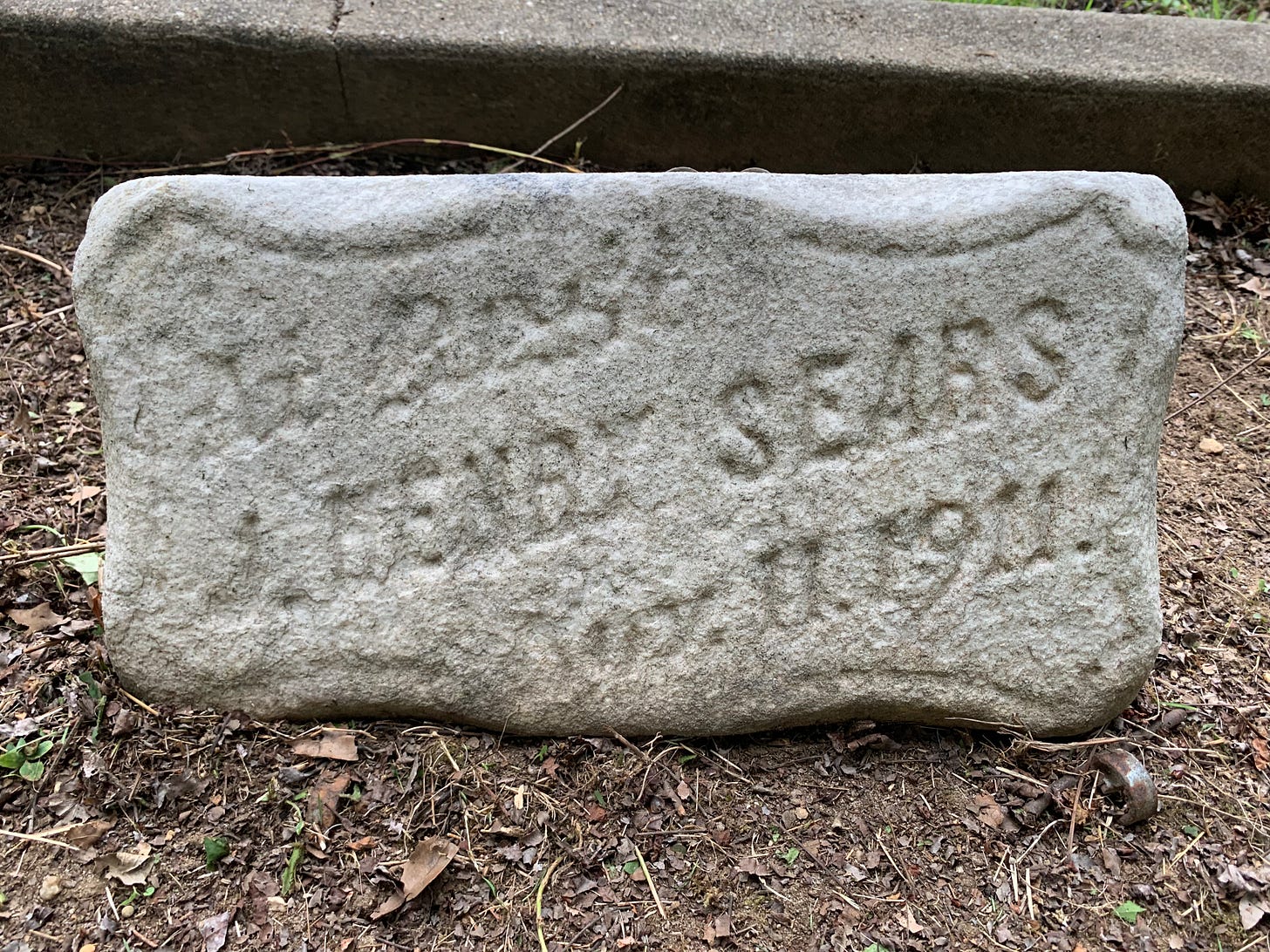

It’s the largest stone in the plot that contains six other markers—all of Robert Damell’s family members

Actually, and to be more precise… the plot actually belongs to John Henry Sears and everyone in there is his family, including Robert Damell. So let’s start with J. Henry Sears.

Sears/Taylor

John Henry Sears of Gloucester County, Virginia came to Richmond in 1861. Or maybe it was 1865. The sources are not clear. If 1861, it might have been to accompany his enslaver (a white man also named John Henry Sears) toward military duty, or toward a new life with a new wife the young white man had just married that year. If 1865, it might have been in the mass migration of freedpeople from plantation to city, no longer constrained by the demands of white people. (He sometimes shows up as J. Henry Sears and sometimes just as Henry. I’m going with the later here.)

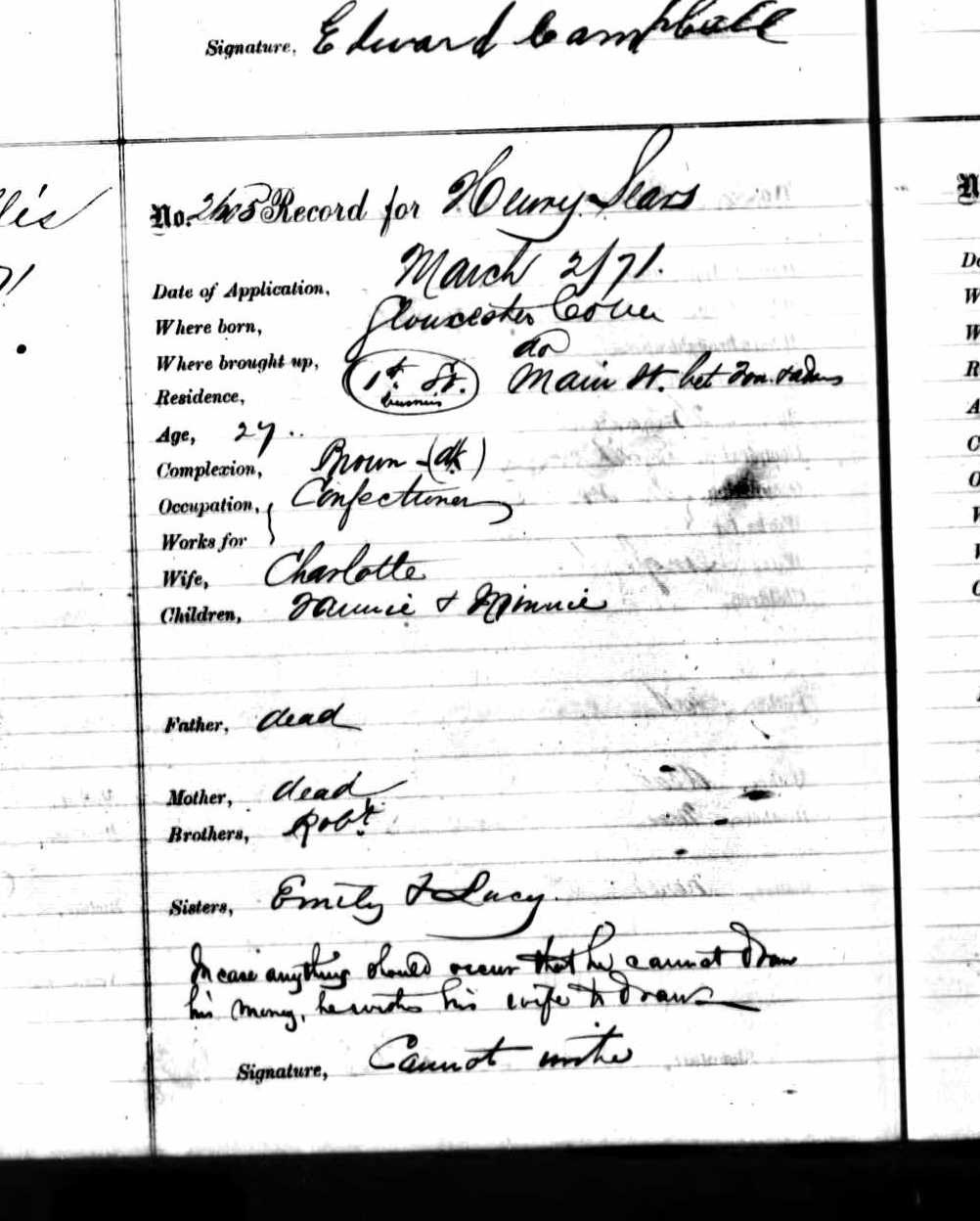

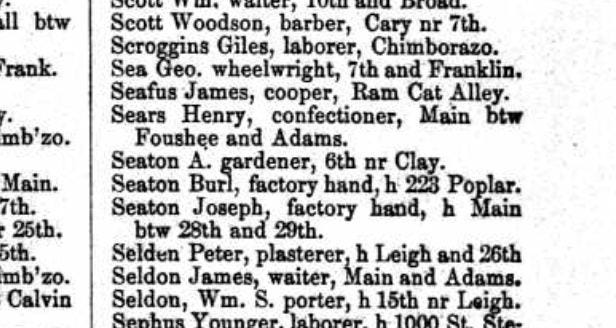

Either way, Henry met and married Charlotte Wood (of Charlottesville), who may have come to Richmond also because she could. He worked as a porter and a confectioner and she a domestic servant while carrying the couple’s first child. Fannie was born in 1868. Henry opened an account with the Freedman’s Bank in 1871 and listed his family as beneficiaries should he die. They lived on Main Street between Foushee and Adams.

Henry and Charlotte moved about the city just as often as he changed jobs (a driver one year, a waiter another, and an “oyster-opener” at another). By the time Charlotte gave birth to her fifth child (of at least thirteen) they lived at 101 W. Jackson Street in Jackson Ward.

I can’t find too much on Henry besides what’s in the census. (Reminder that I’m doing all this from my couch with basic digital databases… there’s more out there.) He did show up in 1894 as a pall bearer for the True Reformer Jane Chamberlain, alongside Ben Scott… a fellow I really need to write about at some point. So he’s hanging out with True Reformers and Ben Scott (and Charlotte was a member at Ebenezer Baptist) so that, at least, tells me he’s plugged in to the whole Jackson Ward set. (That’s Richmond’s Black middle and upper class that gravitated around banking, journalism, medicine, preaching, and countless blue collar jobs in one ward of the city.)

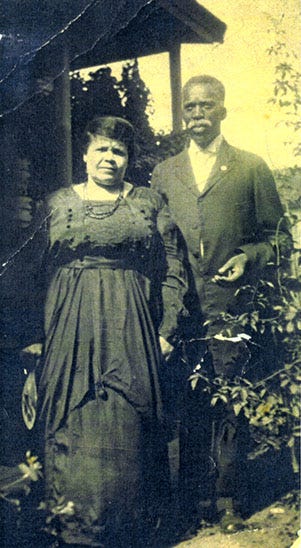

Eleven years later Fannie Sears married Robert Damell, who had returned home to Richmond from ten years in the Army and who worked as a laborer.

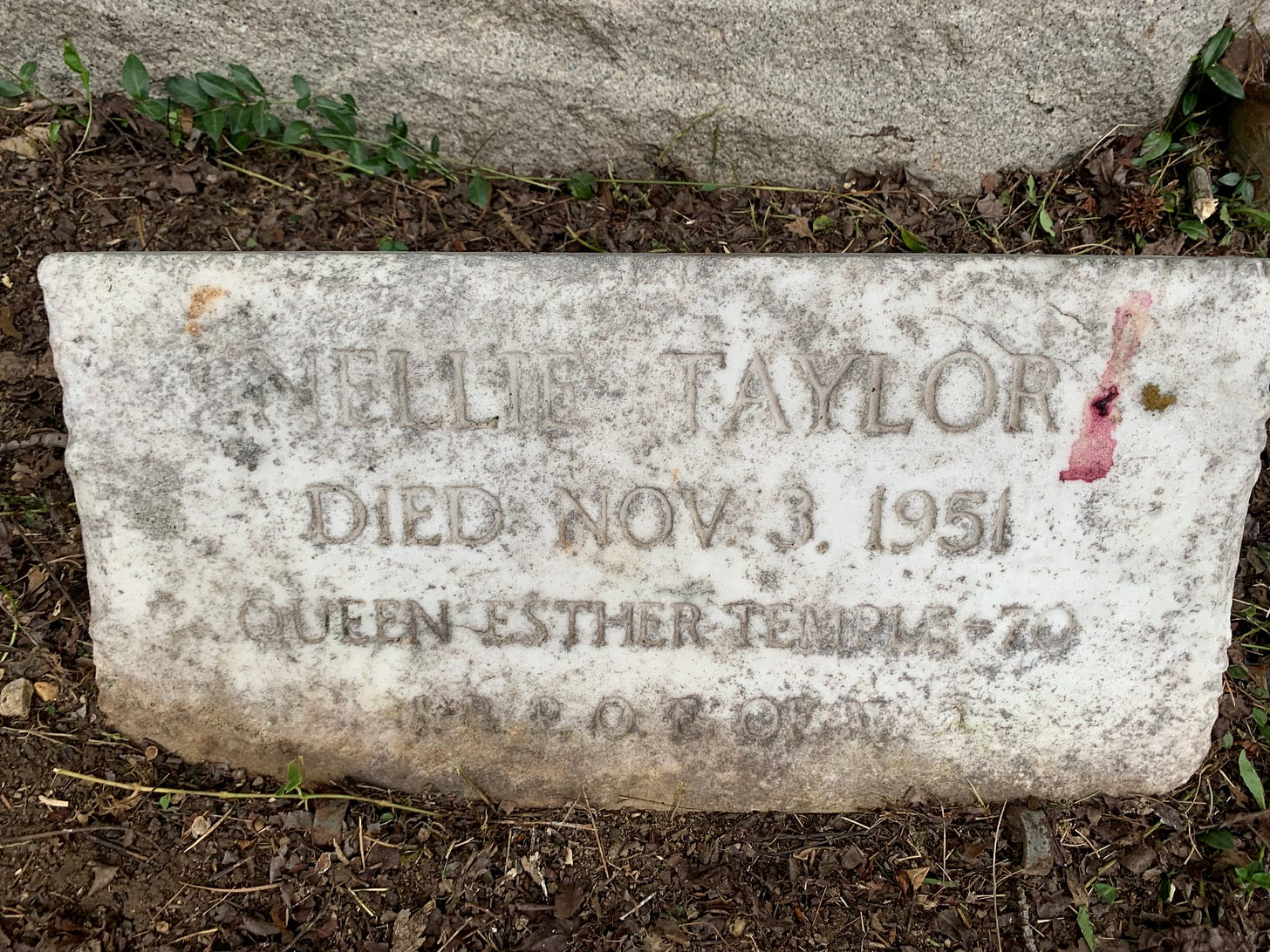

Fannie’s sister Nellie is also buried in her father’s plot.

Damell/Dammalls

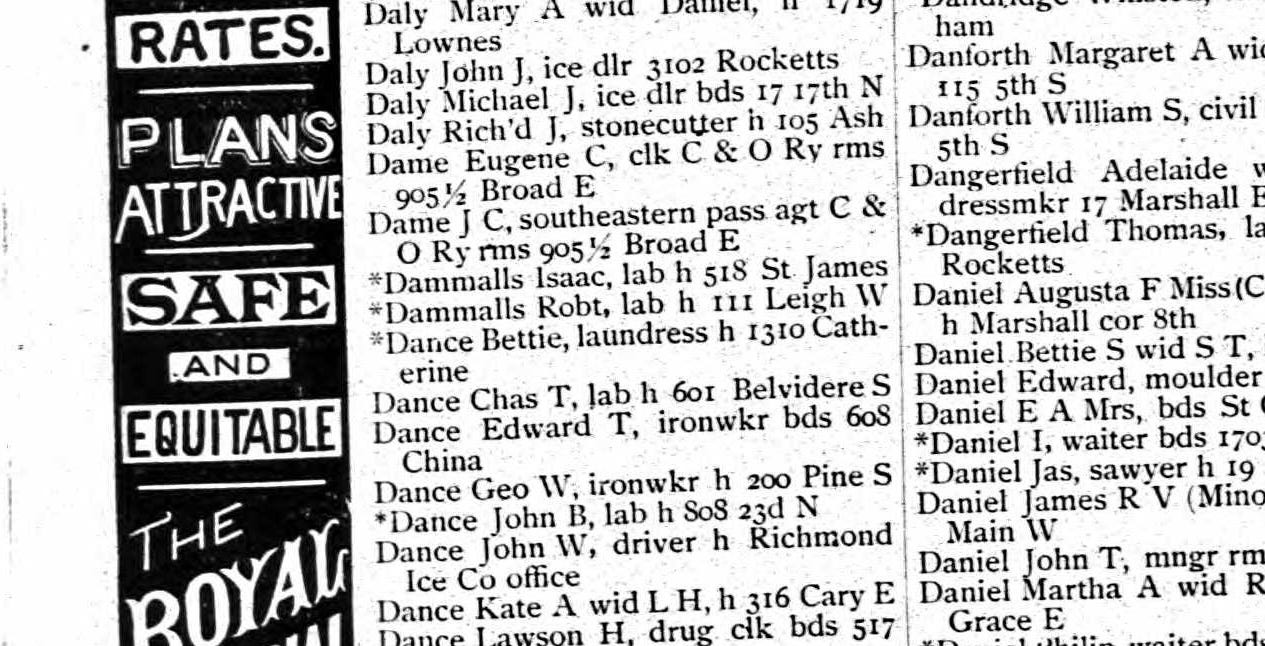

He lived on N. 8th Street in Navy Hill for a while, and at one point Isaac and Robert lived on West Leigh Street among the Sears clan. In fact, I’m not certain they didn’t share a duplex at one point. So it was no surprise that Robert met and married Fannie Sears in 1893. The newlyweds lived on Price Street just around the corner from 110 West Leigh. Eventually, they lived at that venerable address.

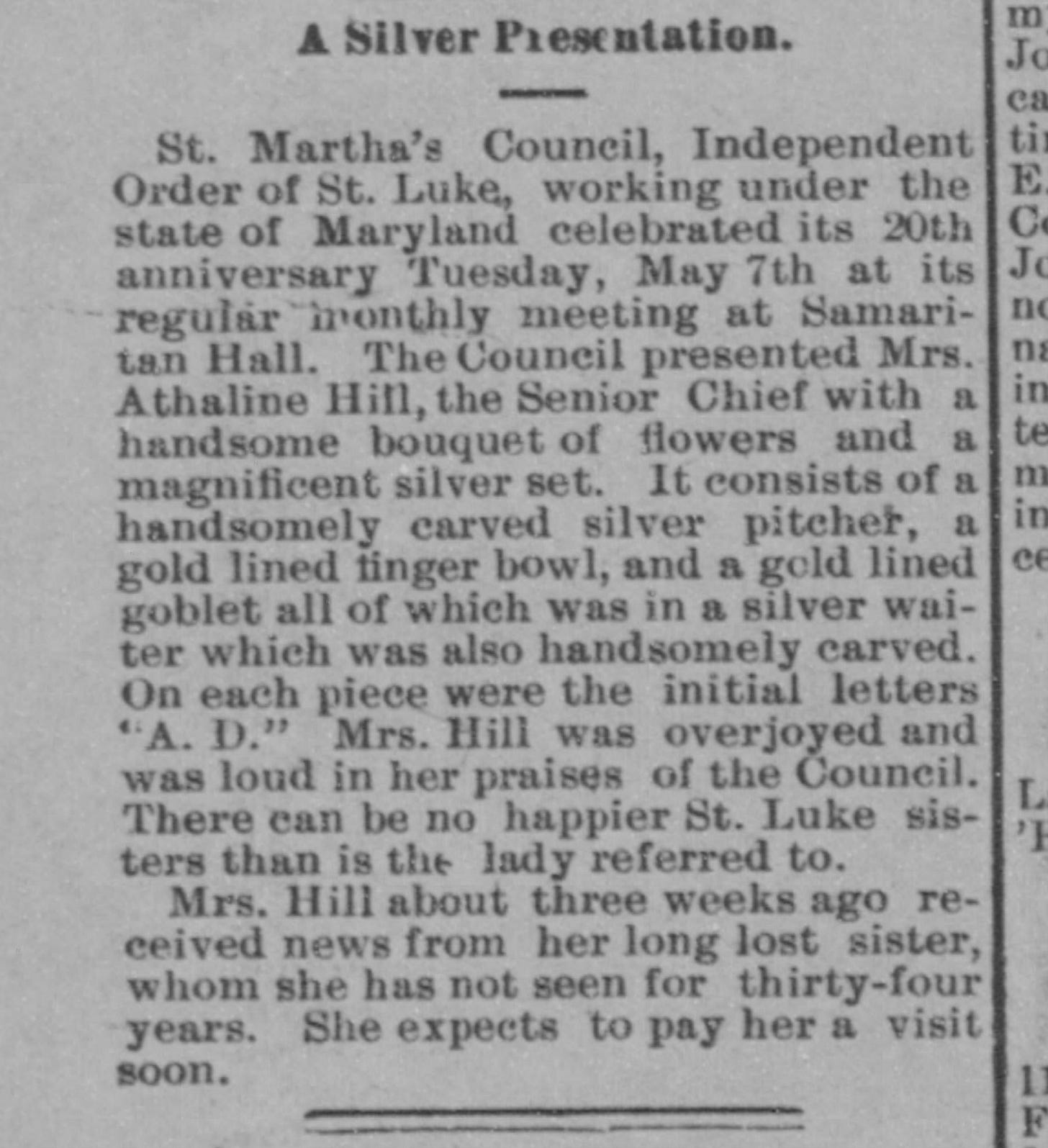

Robert and Isaac Dammalls’ sister Athaline was born in 1855. At that point, the family apparently lived in Lancaster County, Virginia. I’m not entirely clear at all if the Dammalls were enslaved or free, or if they came to Richmond as a family after emancipation, but three of the four children ended up here. Athaline’s early years are obscure. At 16 years old she married 41 year old James T. Hill, a laborer active in Ebenezer Baptist Church.

If those dates are precise, the Dammalls lost track of their sister in 1861. I have no evidence about what happened, but it’s not hard to imagine that it was a family separation via a slave sale.

The eight children—and the countless cousins they all produced—went far and wide. I am uncertain about the chain of migration that took some to Nashville, some to Richmond, and some to Baltimore… but those were locations that hosted significant institutions of higher learning for Black Americans and the Martin and Williams cousins became associated with.

The circumstances are details are not clear, but by the late 1930s the Henry, Sr., Charlotte, and Henry, Jr. had moved to South Hill, Virginia, where Dr. Martin had possibly opened a clinic. Unfortunately, he contracted tuberculosis and died on July 27, 1938. His headstone in Henry Sears’ plot is dedicated to “our doctor” and inscribed by “Southhill friends.”

But that was not the end of the entanglement between Charlotte and Henry’s family. For a time she lived with Benjamin and Nellie Taylor, but two years later she married Henry Martin’s nephew George Arthur Williams (John Henry Williams’ brother and son of Henry’s sister Elizabeth). They raised Henry Jr. together and she continued a forty-one year career teaching at Carver Elementary in Richmond Public Schools.

When Charlotte Damell Martin Williams died in 1984, she lived in an apartment near Monroe Park on Franklin Street and left several more generations of incredible Richmonders behind her.